|

FINANCING REBELLION: Piracy as a Rebel Group Funding Strategy

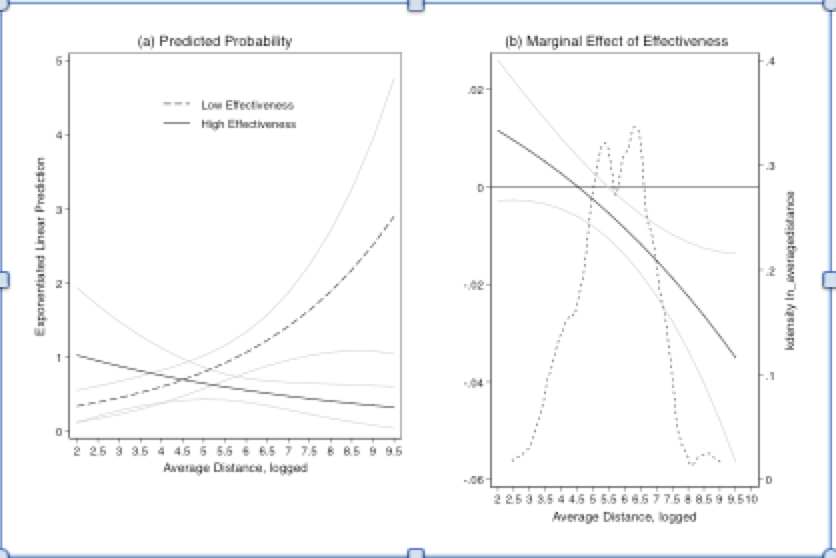

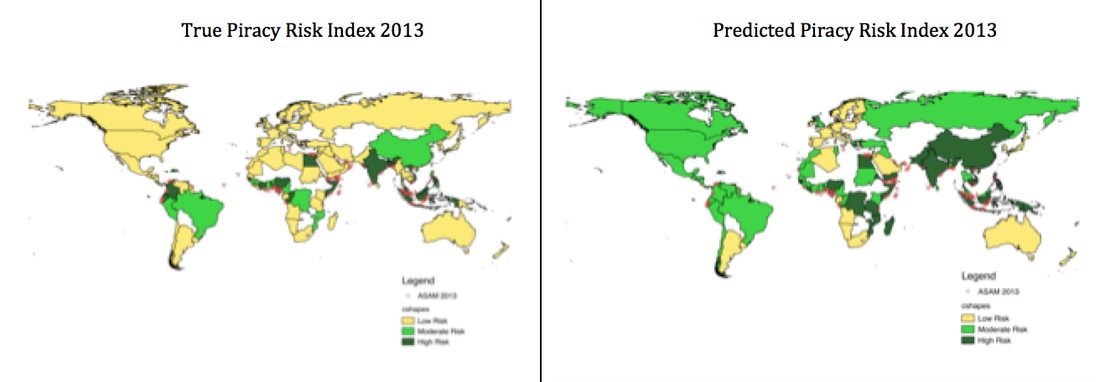

Ursula E. Daxecker, University of Amsterdam Brandon C. Prins, University of Tennessee Extant research shows that resources, such as oil and surface diamonds, increase the risk of civil war onset and contribute to the duration and intensity of conflict. The causal explanations for these relationships remain contested. On the one hand, the unequal distribution of valuable resources within a country and the rent-seeking that accompanies the development and use of a country’s assets may generate grievances among groups that see the exploitation of scarce resources as unfair and allocation determined by political favoritism. On the other hand, lootable resources may finance rebellion by permitting rebel leaders the opportunity to purchase weapons, fighters, and local support. Control of these resources, then, provides a revenue stream that rebel leaders may be unwilling to give up. Scholars have noted that the control of resources can help finance rebellion. The Kimberly Process, for example, acknowledges that alluvial diamonds pose problems for weak and poor countries. The bunkering of oil in the Niger Delta by quasi-criminal syndicates is another case where the black-market selling of stolen oil may help finance anti-state groups. If resource control facilitates rebellion, maritime piracy may be an additional funding strategy used by insurgent groups to finance armed conflict. Anecdotal evidence connects piracy in the Greater Gulf of Aden to arms trafficking, the drug trade, and human slavery. The revenue produced also may find its way to al Shabaab. In Nigeria, increasing attacks against oil transports may signal an effort by insurgents to use the profits from piracy as an additional revenue stream to fund their campaign against the Nigerian government. It is certainly conceivable that the conditions on the ground in the Niger Delta, such as poverty, unemployment, environmental ruin, push young men into arms of both rebel and pirate leaders and so perhaps the foot-soldiers of MEND (Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta) are also the pirates attacking ships in the Gulf of Guinea. We contribute to research on civil conflict by arguing that piracy incidents, i.e. actual acts of looting, increase the intensity of civil conflict. To our knowledge this is the first attempt to document systematically whether piracy contributes to insurgency by funneling critical funds to rebel leaders or altering the strategic bargaining environment. Our evidence from conflicts in Africa from 1993-2010 strongly suggests that maritime piracy increases conflict intensity in both the short and medium terms, and that the effect appears larger than that of either oil or diamonds. Existing studies of piracy focus attention on the institutional determinants of maritime piracy, but neglect variation in governments’ reach over territory. We argue and find that the effect of state capacity on piracy is partly a function of states’ ability to extend authority over the country’s entire territory. Weak governments allow for the planning and implementation of attacks and reduce the risk of capture, but particularly so if sufficient distance separates pirates from political authority. Our empirical analysis of country-year data on maritime piracy collected by the International Maritime Bureau for the 1995-2013 period show that capital-coastline distance mediates the effect of institutional fragility on piracy as we hypothesized. Operationalizing reach by measuring the average capital-coastline distance, we show that institutional variables have little effect when distances are short, but increase piracy substantially for states with long or very long distances. Our findings also show that these conditional relationships are not limited to specific operationalizations of independent and dependent variables. In addition, the models perform well in terms of predictive power, forecasting piracy quite accurately for 2013. The figure below shows the basic interactive relationship between state strength and distance while the map illustrates our forecasting successes and failures for 2013.

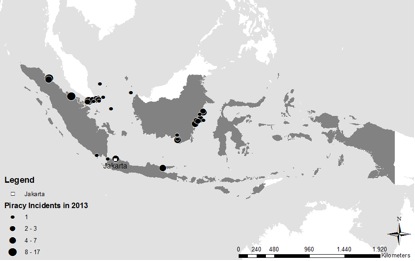

Where do pirates go? Where governments are less effective. Ursula Daxecker, University of Amsterdam Brandon Prins, University of Tennessee-Knoxville The rise and fall of Somali piracy and increasing attacks on oil tankers off Nigeria’s coast has led to increased attention to maritime piracy among journalists and academics. This interest in piracy has produced a number of useful findings supported in case studies and statistical analyses. For example, governments with low state capacity struggle to police coastlines, combat crime, and thus experience more piracy. Poor economic conditions, such as a lack of legal labor market opportunities or a decline in fisheries production have also been linked to increases in piracy. In addition, favorable geography, including long coastlines or proximity to shipping routes, contributes to an environment attractive for prospective pirates. These findings helps us understand why some countries or regions are particularly prone to piracy, but neglect the question of where pirates locate to plan and carry out attacks. Experts note that pirates need sanctuaries on land to operate, but we lack a theoretically informed understanding of how pirates choose locations for organizing attacks. In an article forthcoming in International Interactions, we argue that pirates as strategic, criminal actors weigh the potential gains from successful attacks against the risk of capture when choosing locations. Distance from government power centers or difficult coastal terrain should help reduce the risk of capture and thus influence the calculus of pirate organizations. Indonesian “island pirates,” for example, carry out attacks from areas separated from administrative and economic centers by sea or long roads (Frecon 2014). As shown in the map of piracy incidents in Indonesia below, piracy incidents cluster at significant distance from Jakarta. Data Source: International Maritime Bureau Similar dynamics regarding location have been emphasized for insurgent groups and terrorist cells, where research has shown that conflicts tend to occur in peripheral regions, particularly in more capable states. If pirates consider government strength as we have outlined, it follows that the location of pirate organizations and attacks should be a function of state capacity. As state capacity increases, pirate attacks should be located further away from centers of government power such as state capitals, whereas pirate attacks may occur in close proximity to government power centers in very weak states. We examine this expectation using geocoded data on piracy incidents from the International Maritime Bureau from 1996-2013. Our results show that increases in state capacity result in greater average capital-piracy distances. These findings present a first attempt to systematically explain piracy location. They additionally complement case study accounts noting pirates’ tendency to hide in remote areas. |

Brandon Prins & Ursula DaxeckerSocial scientists researching drivers and consequences of modern maritime piracy. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed